This post marks the first of a series of articles tackling the subject of psychogeography. But, before we are able justify psychogeography as a topic worthy of a series, we need to provide a definition of what psychogeography actually is. It’s a term which has re-surfaced over the past several years, largely down to figures such as Will Self and Iain Sinclair, but has a much longer history than the pairs urban rambling. In fact, its history has origins centuries before the term was even first coined.

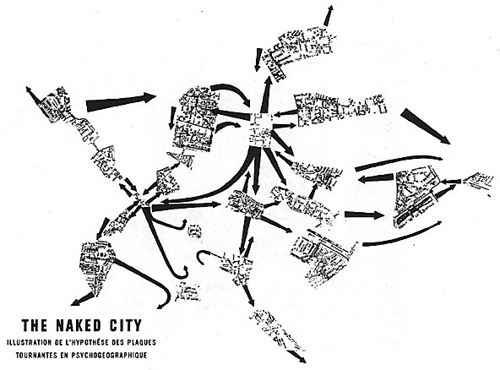

Psychogeography originated in 1950’s Paris with Guy Debord, the creator of the avant-garde group, the Lettrist International. Debord’s own definition is as follows:

“The study of the specific effects of the geographical environment, consciously organised or not, on the emotions and behaviour of individuals.”

Debord himself said that the definition had a “pleasing vagueness” which is rather convenient considering the wide range of situations the term has been applied to. He attributes the invention of the term to “an illiterate Kabyle” in his essay Introduction to a Critique of Urban Geography. Merlin Coverly, in his book Psychogeography, offers a slightly expanded definition:

“And in broad terms, psychogeography is, as the name suggests, the point at which psychology and geography collide, a means of exploring the behavioural impact of urban place”.

The psychogeographic movement has its roots in 1950's Paris with Guy Debord

While the term originated in the 1950’s, we can go much further back to gothic representations of the city, and even as far back as Defoe, who could be said to be the progenitor of a psychogeographic analysis of urban space. For psychogeography as a movement is essentially the tale of two cities: London and Paris.

Paris exists as the home and birthplace of the term while London has long been inhabited by what are predominantly psychogeographic ideas. Figures such as Blake, de Quincey, Robert Louis Stevenson and Arthur Machen were all responsible for an imagining of a city that had a spirit of place, and looked for ways to experience what were familiar surroundings in new and insightful ways. They essentially were experiencing their city in a way the movement in Paris would be describing years later.

We can find the term creeping its way into the mainstream of language. Jenny Colgan wrote an article for The Guardian in August 2012 called Jenny Colgan: what I’m thinking about... the psychogeography of Edinburgh. At no other point in the article is the term psychogeography used again, and yet it managed to find its way into the headline, the most prominent of locations. It’s as if there is no need for explanation and the word is an everyday one. The article itself reiterates much of how we’ve come to understand the term, addressing the nostalgia we can feel walking around certain urban landscapes. Colgan writes that “(I) am constantly suffused with a melancholy sense of something lost... Edinburgh is special. Perhaps because it is a walking town.”

There is a strong link between the practice, if we can call it that, of psychogeography and walking. Because how else are we to really experience a landscape than on foot? How else will we capture the sights, sounds and smells without meeting them face to face?

We’re painting a rather gothic portrayal of psychogeography in this brief introduction that shows it as being the school of thought of the wanderer and traveller; of the city dweller wishing to derive some meaning from the banality of the tedium of their environment; and the writer who imaginatively reworks the city, exploring ways in which the imagination can transform our surroundings into something new.

Defoe's Journal of the Plague Year provides "the prototype psychogeographical report" with an urban wanderer reporting on his observations of a re-imagined London

But if we cast our mind back to the two original definitions we gave at the beginning of this article we will find a much broader take on the term which is how we will be continuing its discussion as this series moves forward. For us, psychogeography is the study and discussion of how our environment influences our mood, and our behaviour. We hope to place a spotlight on this sort of discussion as it is us, as human beings, that the urban space is designed for. And there is nothing that really defines our experiences more than our psychological condition, our thoughts and our feelings. When designing an urban space we must place the human condition at the forefront of our considerations and look at ways in which we can promote the feelings we wish to illicit in our designs.

Unlike the contemporary psychogeographers, we do not wish to simply record our experiences and observations of the urban environment, we wish to change it

Edinburgh, like London and Paris, is a city of the heart. And good urban design, which is considerate of the way our environment can make us feel, can provoke as similarly strong or poignant emotions in us.