Blog

In this two-part series of guides, experts from Marshalls and the Mineral Products Association (MPA) explore the topic of tactile paving in depth. Together, we dive into the history of tactile paving materials and examine why, where and how tactile ground surface indicators (TGSIs) are used in commercial development projects.

For additional guidance on specifying tactile paving within industry regulations, you can read part two of the exclusive interview between Mark King and Colin Nessfield and enquire about Marshalls’ series of paving CPDs.

What is tactile paving?

Before we unpack tactile paving in more detail, we first need to understand what it actually is. Tactile paving - also known as tactile pavers, tactile ground surface indicators (TGSIs) or detectable warning surfaces - is a system of profiled ground surface features that are engineered to assist individuals with visual impairments or blindness when they are navigating public spaces.

The tactile indicators built into the paving materials provide physical cues for people with partial or no sight, helping them detect changes in their immediate environment and traverse inconsistent ground conditions safely. These environmental changes can include approaching obstacles (i.e. street furniture), pedestrian crossings, the edges of platforms (i.e. at train stations), steps or kerb edges.

The inclusion of tactile paving in commercial settings sits alongside inclusivity tactics such as external stair-nosing in broader efforts to create safe, accessible public spaces that are equipped to meet the varying needs of users.

In conversation with Marshalls and MPA: Introducing tactile paving

Mark King (MK): Hi Colin, it’s great to be speaking with you. Our focus for today is tactile paving materials, so would you be able to explain a little bit about your involvement with the wider subject area?

Colin Nessfield (CN): Of course. I’m a concrete technologist and currently the President of the Institute of Concrete Technology - the professional body that represents and promotes the practice of concrete technology worldwide.

I am also a long-serving member of the BSI committee for paving units, having spent more than a decade working on the dedicated paving standards division. As part of my role here, I act as the primary liaison between the committees for Paving Units and Kerbs (B/507) and the Design of an Accessible and Inclusive Environment (B/559). This committee is responsible for the inclusive and accessible design of both the inside and outside of buildings.

MK: Those are some credentials! If we move onto the question of where the idea for tactile paving came from. Where did it originate, and how did it come to be?

CN: In 1965, a Japanese inventor named Seiichi Miyaki created what he then referred to as Tenji Blocks. He developed these tactile paving blocks to help a close friend who was losing his sight but kept his work largely private until 1967 when the material innovation was first used in streets near the Okayama School for the Blind in Okayama City.

MK: How did it spread from those beginnings, and when did it appear in the UK?

CN: Well, it attracted slow but continued attention worldwide throughout the 1970s and 1980s as developers sought to create more accessible public spaces. It wasn’t until the 1990s that the UK, Australia, and the USA began to adopt tactile paving.

Initially, the uptake was within the transportation sector - railways and bus stations, etc - but tactile paving materials gained traction more widely at the turn of the millennium.

At this point, commercial developers and town planners began incorporating tactile paving into environments more widely, using it to alert people with visual impairments to approaching junctions, oncoming traffic, hazards and obstacles. The usage of tactile paving in the UK has been increasing since the 2000s, with more and more applications relying on its tactile properties to create safe spaces.

MK: What different types of tactile profiles are available, how did they come about, and why are they used for particular applications?

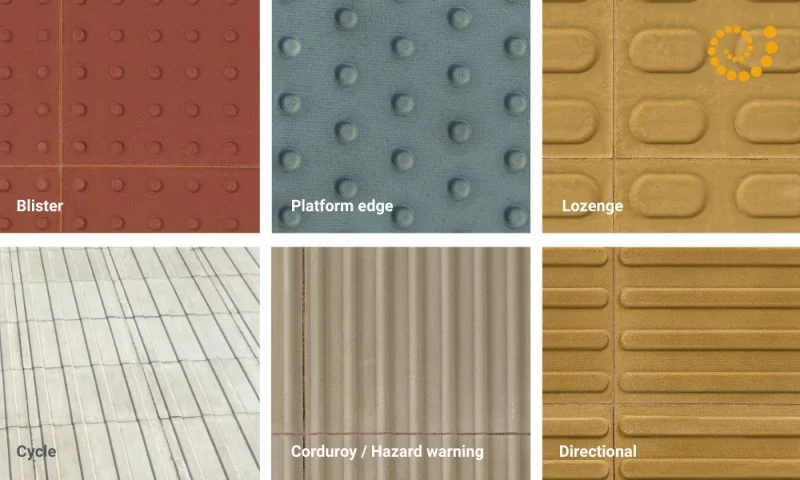

CN: Initially, there were blistered profiles (with raised flat-topped domes) and directional profiles (with long raised bars).

In terms of applications, long bars were used to either direct somebody when the raised bars were aligned with the direction of travel or warn them of a hazard if the bars were across their path. Profiles with long bars can, therefore, give direct messages to users with impaired vision.

By comparison, blistered paving profiles alert users that they are approaching some kind of hazard - either pedestrian crossings with dropped kerbs or the edges of rail and tram platforms.

Ultimately, there are only so many patterns that you can create in a paving material before the patterns themselves become confusing for the users

Now, there are six common profiles of tactile paving, but they all stem from Miyaki’s original concept. Over the years, material technologists have extended the core principles of tactile pavers to create the profiles needed to fill the gaps we have.

I’ll run through each of these types briefly.

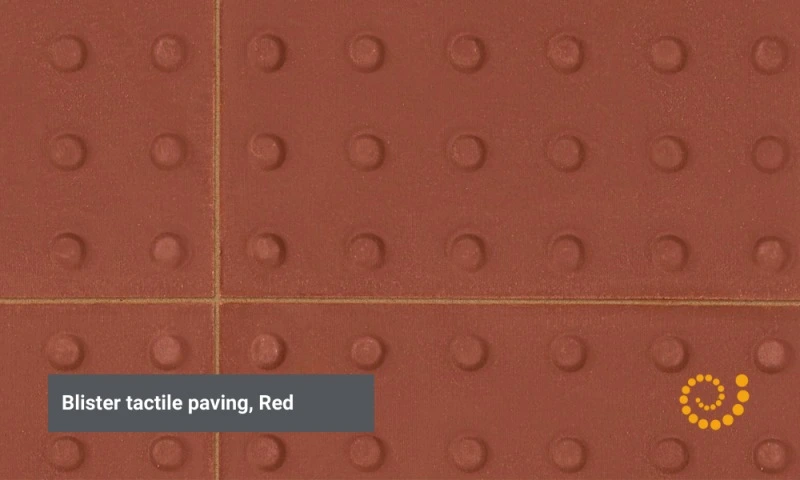

Type 1: Blister tactile paving

Generally, blister paving is used at roads or other crossings, and the red colour specific to blisters is used to denote a controlled crossing point. So that's being quite specific to say that somewhere around here is probably a button or a lever that you can activate in order to control the traffic.

Whereas all the other colours are for uncontrolled crossings where you're relying on the traffic, either the absence of it or the goodwill of the driver to let you by in order to cross.

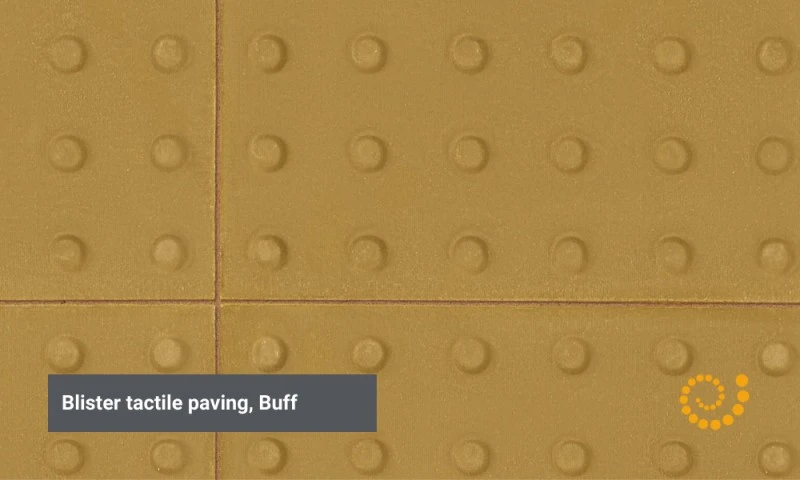

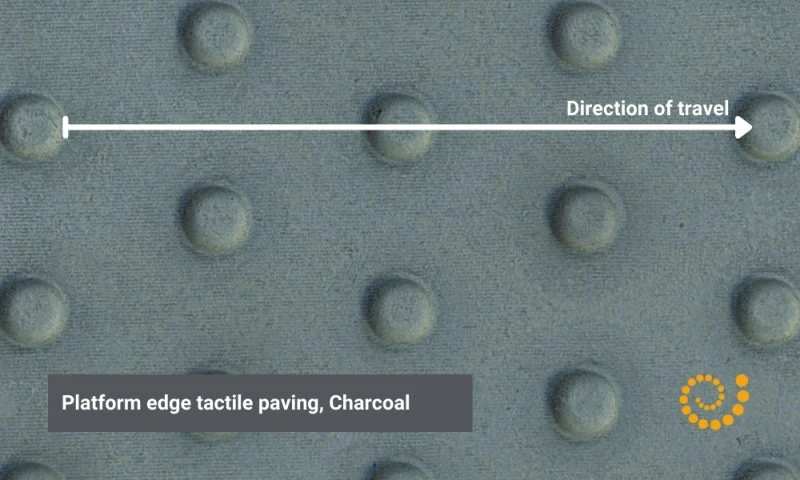

Type 2: Platform edge blister paving

The next version of that is the off-street platform edge blister, and the main difference is for crossing points, where the blisters are aligned in format, whereas the platform edge blisters are off-centre.

Some people refer to it as the blisters being ‘staggered’, so they're not square, and this type is used on railways, light, rapid transport systems and wherever you've got a warning that's off-road. So, typically you're talking about a train station, and it's not in a street environment. These pavers will normally be buff or yellow, basically any colour but red.

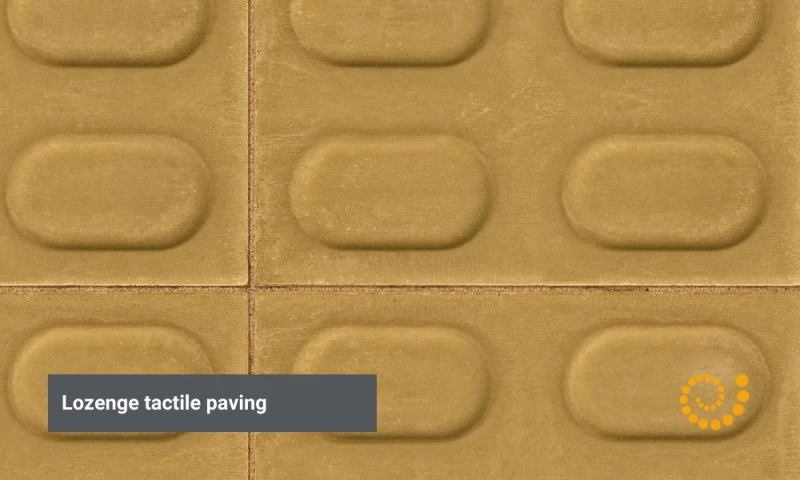

Type 3: Lozenge paving

If you have, for instance, light rapid transport systems, tramways, etc., you'd use the next product, an on-street platform edge, sometimes referred to as a lozenge.

Those with the big lozenge shapes across them indicate that you are at a boarding point or warning of crossing rapid transit systems and tracks.

Type 4: Cycle tactile paving

The next one on the list, we've got the cycleway and footway tactile paving. These have bars that are used to indicate the pedestrian and cycle sections of shared cycleways, and the bars are aligned much as I described earlier for the cycle portion of the cycleways they are aligned in that direction of cycle travel. For the pedestrian half, there'll be aligned across the direction of travel to make it uncomfortable for the bicycle to go over.

So, having the same product laid in a different orientation says, "use this side for easy access and try not to use this side as it's the pedestrian half.”

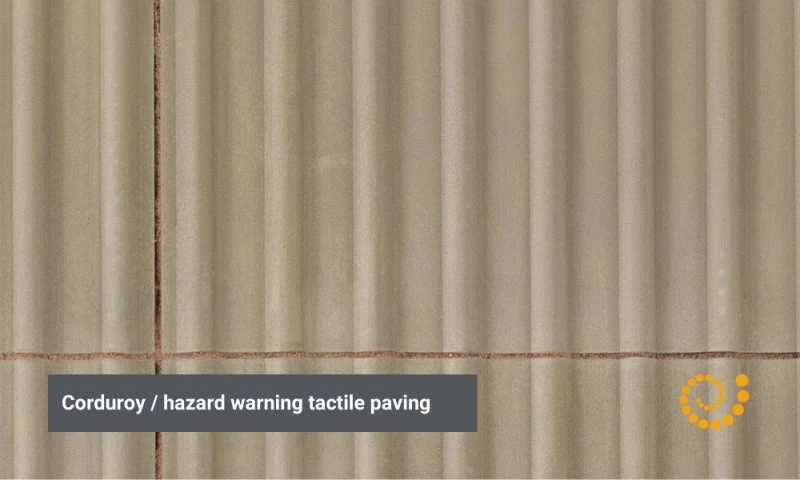

Type 5: Corduroy or hazard warning paving

In a similar profile to the cycle paving, you have corduroy or hazard warning paving, which would be installed to run across the approach to a hazard, such as obstacles in the middle of an open area or at the top or bottom of a flight of stairs.

It's very important that the pavement contrasts with its surroundings and stands out.

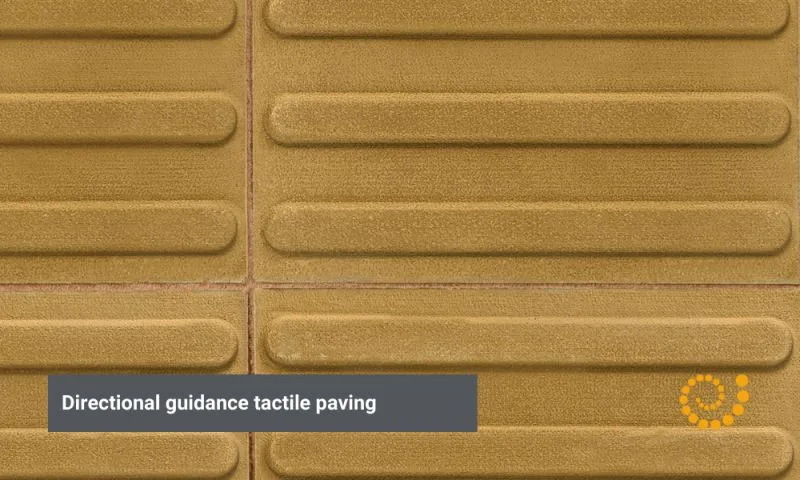

Type 6: Guidance paving

The last of the six common types is guidance paving. It's rarely used, but it guides users around obstacles in open spaces or across large open spaces. If the user knows that a pathway takes them from one corner of a large square to another, then it eases their path.

In terms of most documents, there is a seventh product that's included, but it's not actually a tactile surface indicator. It's used in cycleways as a cycleway delineator block; it simply runs between the two halves of the paving, separating pedestrians from cyclists. It's a regularly used product, but it's not officially a tactile paving indicator.

They're the products that have derived from the two concepts that were first invented: bars to indicate passage or no passage and blisters to indicate potential hazards.

MK: Thanks for sharing all these insights about tactile paving, Colin. We’ve covered a lot of ground and answered some fundamental questions about the types and applications of tactile paving materials. I look forward to chatting with you again about the regulations and specifications of tactile paving.

If you want to get request a CPD with our team, you can find the tactile paving topic in our CPD library.